Recent surveys in the United States demonstrate the substantial presence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in our health care system. Commonly used CAM therapies include hypnosis, manipulation, homeopathy and acupuncture [1] with the use of herbal medicine, massage, self-help groups, megavitamins, energy healing and homeopathy increasing dramatically in the 1990s[2]. In 1997 visits to CAM practitioners exceeded visits to primary care physicians by more than 243 million[2]. Perhaps more shocking is the amount of money spent on CAM in the United States. Eisenberg and colleagues conservatively estimate that $21.2 billion was spent on CAM practitioners in 1997 with more than $27 billion spent out-of-pocket on CAM practitioners, herbal products, megavitamins, diet products, books, classes and equipment[2].

People use CAM for a variety of complex and personal reasons[1]. Conventional medicine with its sophisticated technologies may not be trusted, and viewed as impersonal and driven by profit. In chronic illness, the inability of biomedicine to cure disease may lead people to seek alternative therapies to deal with pain and other symptoms. CAM is also often viewed as "natural" and therefore more safe than conventional medicine. However, CAM is not used in isolation. Most users of CAM also consult traditional health care professionals such as doctors who may know little about alternative therapy and probably don't ask their patients about CAM use[3]. And only 35% of people discuss their use of CAM with their doctors and most people using an alternative therapy do so without even consulting an alternative provider[2]. This “unsupervised use” is quickly apparent by surfing the web or visiting the local grocery store where shelves of herbal products are readily available. Unfortunately, this can lead to significant problems, such as combining prescription drug use and herbal products or megavitamins with the potential for significant adverse effects. Eisenberg and colleagues estimate that 15 million adults are at risk for adverse interactions because of concurrent drug, herb and/or megavitamin use[2].

This phenomenal growth in CAM presents a challenge for allopathic or traditional medical and nursing educational programs for a variety of reasons. First, most allopathic programs already have dense curricula due to the explosion of biomedical knowledge related to pharmacology, pathophysiology, disease management and disease prevention.

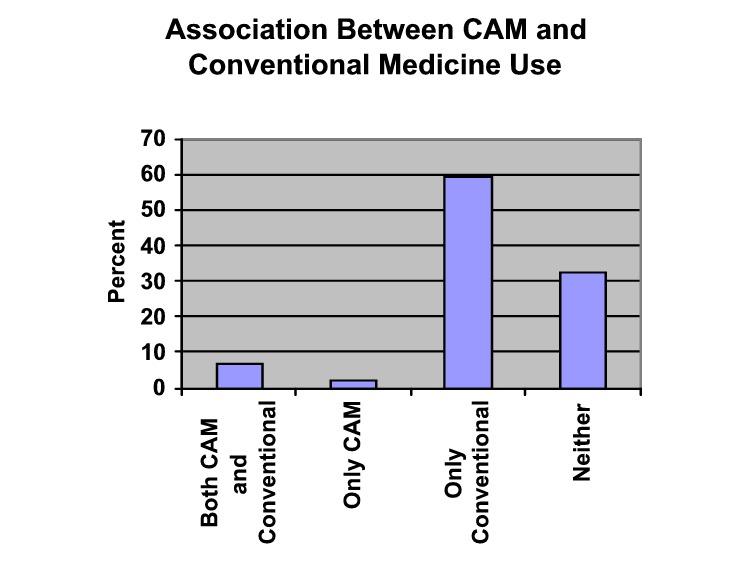

Source[4] |

Second, no clear guidelines exist on what should be included in NP programs. The National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties simply recommends that content on CAM should be included in the curriculum[5]. The most challenging issue is that many CAM therapies have quite differing philosophies, viewing human health as a complex interaction between mind, body and spirit, that are in direct opposition to the world view of mainstream medicine, which views health from a biological perspective. Moreover, many CAM therapies lack clinical and scientific evidence supporting their use. In biomedicine, "evidenced-based practice", in which efficacy of interventions is documented by sound clinical research, is a hallowed and rigid gold standard. Consequently, there are significant barriers to incorporating CAM content including lack of |

time and money as well as the lack of clinical and scientific evidence supporting CAM therapies. Despite these barriers, a growing number of medical schools have courses on CAM, although these are typically elective [6], [7]. "What is more, considering all the dubious and disparate theories and practices gathered under the banner of alternative medicine, I don't see how our medical schools could make sense of such a hodgepodge, much less unify it with conventional medicine."[8] Arnold Relman, MD, Editor-in-chief emeritus of the New England Journal of Medicine. However, little is known about CAM content in nursing programs. At this point, few NP programs (38%) have either elective or required CAM content[5]. The faculty in our FNP program has incorporated some content on CAM, but not systematically and, like other FNP programs, our curriculum is packed with little room for new content. "Members of our profession are concerned about nurses who are rushing in to fill the vacuum created by the escalating demand for alternative practitioners. . ."[9] Lois Biggin Moylan, PhD, RN.

As practitioners and teachers we are in a quandary knowing through experience that some CAM therapies are beneficial and that our patients are using them extensively, but lacking basic knowledge of CAM and feeling unsure how to provide the best care for our patients when CAM may be "foreign" to our world view. It is not a matter of simply teaching students about CAM therapies, e.g., what is acupuncture and when might it be appropriate to recommend to a patient. NP students need to be able to know how to talk to patients about CAM, e.g., how to interview patients so they get needed information about how persons view their health and what types of convention and CAM therapies are used or deemed acceptable by the patient. Moreover, students need to know how to synthesize knowledge about conventional and CAM therapies in such a way that an acceptable and efficacious plan of care can be established. In other words, students need to know what specific CAM therapies are, but they also need background information about culture and diversity (what patients believe about health and health care), nursing philosophy (how do nurses intervene with their patients), research methods (what evidence supports use of this therapy) and legal and ethical issues (how are CAM providers regulated and how can NPs refer patients to them)."My impression is that many patients now going to alternative practitioners, if given a choice, would prefer to go to a physician who had basic medical training and was also knowledgeable about and open-minded about other treatment options, who could act as a guide or an advisor in making difficult treatment decisions."[10]. Andrew Weil, MD. These issues are addressed in a variety of courses in the typical NP curriculum. For example in our FNP program at UW, students learn about culture and health beliefs, especially related to rural environments, in one of our core courses on rural health and health care. They learn about critical thinking and how to interview patients in another course on clinical decision-making and advanced assessment. Consequently, ensuring that FNP students meet basic competencies in relation to CAM impacts the entire curriculum, not just one course.

No commonly accepted definition of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) exists and how CAM is defined most likely depends on who you are. If you are a physician with a strong biomedical philosophy, most all therapies not involving medication and/or surgery will be alternative to medicine. However, for a nurse with a very holistic philosophy, therapeutic touch may not be complementary or alternative at all, but within the normal range of therapeutic options.

Generally a broad array of healing philosophies, approaches and therapies are included in definitions of CAM. Physicians have defined CAM as "interventions neither taught widely in medical schools nor generally available in US hospitals"[11]. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) in the National Institutes of Health uses a similar definition and includes treatments and practices not generally reimbursed by medical insurance companies NCCAM Site Definition These definitions are problematic because they fail to take into account changes as more CAM is incorporated into health professional education and health service delivery[12]. The NCCAM has recently developed a classification system for CAM based on specific services, rather than training, type of provider, or location of service. CAM Classification Seven categories of CAM are identified: mind-body medicine, alternative medical systems such as Traditional Chinese Medicine, lifestyle and disease prevention, biologically-based therapies such as herbs, manipulative and body-based systems, biofield, and bioelectromagnetics. In this classification, therapies are viewed from more alternative to less alternative.

Portfolios increasingly are seen as a way to document the scholarship of teaching and learning. Hutchings proposes that portfolios be used as an "argument, case, a thesis with relevant evidence and examples cited, rather than a miscellaneous collection of things" and that the author of a portfolio should "Aim for coherence around some central organizing principle(s)"[13]. Several types of portfolios have been used in higher education: 1) student portfolios in which students document learning and attainment of course objectives, 2) teaching portfolios that focus broadly on the evaluation of faculty teaching in general, and 3) course portfolios where a faculty evaluates teaching and student learning in a specific course. Such course portfolios have proved very valuable for describing the anatomy of the course, documenting the natural history or evolution of a course, examining the course ecology by evaluating the course within its programmatic or curricular context, or documenting the use of a course as an investigation[14].

This portfolio extends the idea of using portfolios to document the scholarship of teaching and learning to examining how a specific concept of interest is or is not addressed and reinforced throughout a curriculum, not within a specific course or through the teaching of an individual teacher. Axiom: The ideal portfolio is both brief and complete. Theorem: No ideal portfolio can exist. Hutchings argues that a portfolio must "have a controlling idea, an organizing principle, around which the right materials can be selected, organized and reflected upon"[15]. In this case, the organizing principle was how the concept of complementary and alternative medicine was addressed and reinforced in our family nurse practitioner curriculum at the University of Wyoming.

Lee Shulman observed that most teachers can be "superbly Socratic once a month. . .the real embarrassments of pedagogy are at the level of the course: the course that just doesn't quite hang together. The course where the students can't quite figure out how what you're doing relates to what you're doing next week, or why a major assignment is connected to the central themes of the course. The most holistic, coherent, integrated aspect of teaching is often where we fail" [16]. I heartily agree and would take that argument once step further. Where it is easy to fail in higher education, especially in professional disciplines, is creating and maintain holistic, coherent, integrated curricula so that students understand how what we are doing in this course relates to the other courses they are taking and what they will do in their professional practice.

Lee Shulman describes a scholar as "someone who is communal; she not only cannot but must not keep secrets. Scholarship entails a responsibility to 'pass it on', to exchange what you have learned, what you have found, what you have invented, what you have created, with the other members of your community, assuming that they will do the same for you" [17]. "Teaching, like sex, is something you do alone, although you're always with another person/other people when you do it;. . . and people rarely talk about what the experience is really like for them, partly because, in whatever subculture it is I belong to, there's no vocabulary for articulating the experience and no institutionalized format for doing so." [19] Jane Tompkins, 1990. This portfolio was created as a mechanism to make my work on making sense of complementary and alternative medicine in a nurse practitioner program "public, susceptible to critical review and evaluation, and accessible for exchange and use by other members of one's scholarly community"[18].

What communities of scholars was this web-based portfolio intended to reach? The most immediate audience for this portfolio is UW School of Nursing faculty and students. In addition, nurses teaching NP programs also are encouraged to view the site. The scholarship of teaching and learning is "deeply embedded in the disciplines; its questions arise from the character of the field and what it means to know it deeply"[20]. Consequently, it is vital to involve nursing colleagues in the review and evaluation of this porfolio. However, it is my hope that others outside of nursing will benefit and at the same time provide me with valuable feedback. Colleagues outside of nursing, including fellow inVISIBLEcollege participants at the University of Wyoming and CASTL scholars from across the United States and Britain, are vital to the review and critique of the web-based portfolio.

I am an associate professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Wyoming (UW) . I have been at the UW since 1992 teaching public health nursing and family nurse practitioner (FNP) courses. I have experience teaching at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. I also coordinate the graduate level family nurse practitioner program. In addition to teaching, I have done research on the experiences of chronic illness. I also maintain an active practice as a FNP. I currently work in Student Health Services at UW and at a free indigent clinic in Laramie, called the Downtown Clinic.

Mary E. Burman, School of Nursing

Mary E. Burman, School of Nursing

What's a family nurse practitioner?: Family nurse practitioners (FNPs) are registered nurses that have completed a formal program of advanced preparation in primary care. Their responsibilities include health assessment, ordering of diagnostic tests, management of common acute and chronic illnesses with pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapies, teaching and counseling, health promotion and disease prevention, and consultation and referral as appropriate. Nurse practitioners are licensed in all 50 states.

I have broad experience in applying teaching strategies. Nursing is foremost a professional discipline and we place equal emphasis on academic and clinical teaching. During my tenure as coordinator, the team of faculty teaching in the FNP program has explored a variety of active learning strategies to facilitate development of clinical reasoning skills in our students. We have used case studies in class, internet case studies, problem-based learning, role-playing and role modeling, and think aloud exercises in which we talk through a complicated case with the students. I was involved in an interdisciplinary faculty group (nursing, pharmacy, social work and medicine) that developed a standardized patient program in which lay persons are trained to play a standardized case for students. Standardized patients can be used to teach and evaluate clinical reasoning, interpersonal skills, history taking and examination skills. In addition, our population of nontraditional students also lends itself to a variety of distance learning strategies and I have experience in compressed video teaching and web-based courses. Finally, in the School of Nursing we use team teaching and both peer review and teaching portfolios are used as part of the evaluation process.

I have a variety of connections at the University as well as throughout the country that help as I explore new teaching and learning strategies. The Center for Teaching Excellence (CTE) at the University of Wyoming is an invaluable source of peer support for innovation in teaching. I have participated in a variety of activities through the CTE and I have been an invited speaker on several occasions to discuss active learning methods and strategies used to enhance clinical reasoning. I am a part of an interdisciplinary group of faculty at the University of Wyoming exploring teaching and learning through an ongoing program called "inVISIBLEcollege" sponsored by the Center for Teaching Excellence. I received funding through this group to develop the web-based portfolio. My involvement in interdisciplinary research and teaching projects as the University of Wyoming are also a significant resource. I also am active in a variety of nurse practitioner professional organizations including the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) (I am the Wyoming representative), and the National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculty (NONPF) (I am on the faculty practice committee).

The University of Wyoming (UW) is a land-grant institution founded in 1886 and classified as a doctoral-research university - extensive. Located in Laramie, the southeastern part of the state, the University remains Wyoming's only four-year institution of higher learning, serving a geographic area roughly twice the size of the state of New York with a population of about 450,000. Approximately 700 faculty provide education, research and service "to prepare students for a complex world of tomorrow while preserving our state's rich western history". Because Wyoming is a large, sparsely populated state with harsh winter weather, UW has accepted the challenge of making the entire state its campus. The campus in Laramie extends over 785 tree-shaded acres on a high plain between two mountain ranges. UW offers 85 undergraduate and 86 graduate and professional degree programs within the Colleges of Agriculture, Arts and Sciences, Business, Education, Health Sciences and Law. The student population is approximately 9,000. University of Wyoming

Old Main, University of Wyoming Campus

Old Main, University of Wyoming Campus

The School of Nursing is part of the College of Health Sciences, which also includes Pharmacy, Social Work, Medical Education and Public Health, Communication Disorders, Kinesiology and Health, Allied Health, and the Wyoming Institute for Disabilities. Legislation to initiate the Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) program was passed in 1951 with students admitted that fall. The program received initial accreditation from the National League for Nursing in 1955 and has maintained accreditation since that time. A The Master of Science (MS) program accepted its first students in 1980. It has been accredited since 1985. The emphasis of the graduate program is advanced practice nursing in rural health. Currently, three options are offered at the graduate level: community health clinical specialists, family nurse practitioner and nurse educator. In addition, an RN/BSN program is available nationwide through web-based courses. School of Nursing

The family nurse practitioner (FNP) program is a graduate program in the School of

Nursing. According to the ANA's American Nurses Credentialing Center, "A family nurse

practitioner is a registered nurse with a graduate degree in nursing who is

prepared for advanced practice with individuals and families throughout the

lifespan and across the health continuum. This practice includes independent

and interdependent decision-making and direct accountability for clinical

judgement. Graduate preparation expands the comprehensiveness of the family

nurse practitioner role to include participation in and use of research,

development and implementation of health policy, leadership, education, case

management, and consultation." Completion of the FNP program as a full-time student takes two nine-month academic years

plus a summer practicum at the end of the program. There are also part-time

options. Registered nurses with a master's in another aspect of nursing can

complete the post-master's FNP program.After completion of the FNP program, students are eligible to take the

national certifying examinations.

The overall goal of this inquiry project was to evaluate approaches to incorporating complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) into the curricula of nurse practitioner (NP) programs. In other words, to look at "what works" in relation to teaching and learning of CAM in conventional nursing programs. Specifically, I undertook a comprehensive assessment of how the concept of complementary and alternative therapies is (or is not) addressed in our curriculum. Our goal in the FNP program is to help students integrate past clinical knowledge (most students come into the program with quite a few years of experience as a nurse) with academic classroom information on primary care and student clinical experiences in various primary care settings. Fundamental to our program is a strong emphasis on facilitating sound clinical reasoning so that students/graduates accurately assess patient situations and determine appropriate plans of care with their clients. We have a strong primary care focus and have a fairly conventional curriculum.

The outcome of this comprehensive assessment is a "concept portfolio" examining CAM content in our NP curriculum. The portfolio contains selected pieces of evidence along with critical reflection and recommendations about what works in relation to teaching and learning of CAM. This portfolio is web-based so that it can be reviewed by others around the country.

I undertook a comprehensive assessment of how the concept of complementary and alternative therapies is (or is not) addressed in our curriculum.In order to help me get a better view of the "big picture", I used a variety of data sources.

Core competencies attempt to "describe nurse practitioner behaviors upon entry into practice"[21]. The National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties recently updated it's core competencies for nurse practitioners to be used to guide curriculum development and evaluation of NP programs. The newly revised core competencies are designed to reflect the current nature of NP practice, however, they do not address complementary and alternative therapy in any detail. Therefore, a more specific set of CAM core competencies were developed based on the NONPF general core competencies, an extensive review of the literature, family curriculum guidelines for CAM[22], and semi-structured in-depth interviews with NPs and NP educators. The CAM core competencies are currently being validated in a national survey of FNP program directors. The CAM core competencies follow the same domains and format as the general core competencies developed by NONPF.

Domain 1: Management of client health/illness status

1) Elicits information about CAM use from clients in nonjudgmental way.

2) Demonstrates critical thinking and diagnostic skills in diagnosing client problems and

negotiating treatment plans, including CAM, with clients.

3) Demonstrates knowledge of the following commonly used CAM therapies, including basic

theory/principles of the therapy, clinical indications, possible adverse

effects and interactions with conventional treatment, and indications for

collaboration/referral.

a) Mind/body medicine, e.g., yoga, Tai chi, meditation, imagery,

hypnosis, biofeedback, support groups, soul retrieval, music, art, dance

therapy, journaling, and spiritual healers

b) Alternative medical systems, e.g., acupuncture and oriental medicine,

Native American medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, homeopathy, and naturopathy

c) Lifestyle and disease prevention, e.g., electro-dermal diagnostics,

medical intuition, chiriography, lifestyle therapies, and health promotion

d) Biologically-based therapies, e.g., phytotherapy or herbalism, special diet

therapies, orthomolecular medicine, and pharmacological, biological and

instrumental interventions

e) Manipulative and body-based systems, e.g., chiropractic, massage and body

work (osteopathic manipulative therapy, cranial-sacral OMT, reflexology,

Pilates method, polarity, acupressure, rolfing), hydrotherapy, and colonics

f) Biofield, e.g., therapeutic touch, healing touch, reiki

g) Bioelectromagnetics

4) Evaluates CAM therapies in regards to efficacy, safety and indications.

5) Collaborates with CAM practitioners.

6) Arranges for appropriate follow-up for clients using CAM therapies.

7) Performs specific CAM therapies.

a) Herbal medicine for common illnesses

b) Nutritional medicine, e.g., vitamin/mineral supplements.

c) Health promotion

d) Mind/body medicine, e.g., imagery, progressive relaxation, meditation, biofeedback

e) Manipulation, e.g., acupressure for common pain syndromes (low back pain, HAs)

f) Homeopathy for common illnesses

g) Biofield, e.g., healing touch, therapeutic touch

Domain 2: The Nurse-Client Relationship

1) Respects client use of CAMDomain 3: The Teaching-Coaching Function

1) Elicits information about client perceptions of CAM.

2) Communicates health information about CAM using evidenced-based rationale.

3) Negotiates a mutually acceptable plan of care based on the client's preferences in

relation to CAM.

Domain 4: Professional Role

1) Uses nursing theory to clearly delineate nursing approach to client care, including

the role of CAM in advanced nursing intervention.

2) Uses sound judgment when assessing conflicting priorities and needs in relation to

conventional and alternative therapies.

Domain 5: Managing and Negotiating Health Care Delivery Systems

1) Demonstrates knowledge of relevant laws and regulations governing CAM, including practice

acts, training, licensure and credentialing of CAM providers, the Dietary

Supplement Health and Education Act, and malpractice issues related to

collaboration with CAM providers.

2) Demonstrates knowledge of reimbursement of CAM providers.

Domain 6: Monitoring and Ensuring the Quality of Health Care Practice

1) Acts ethically in supporting client's use of CAM, acknowledging principles of

autonomy, beneficience, and justice.

2) Uses an evidenced-based approach to client management by critically evaluating and

using research findings on CAM use and outcomes.

3) Evaluates client responses to health care, including conventional and CAM.

Domain 7: Cultural Competence

1) Respects possible effectiveness of CAM therapies.

2) Acknowledges inadequacies of conventional medicine.

3) Acknowledges and respects own and client's cultural and spiritual beliefs about health and

healing.

4) Understands how cultural and spiritual beliefs affect health behavior, including use of

both conventional and alternative medicine.

5) Understands patterns of CAM use regionally and nationally, including reasons why clients

likely to seek CAM.

This portfolio is organized around the components identified by Hutchings as necessary for a course portfolio[23]. These components were adapted for a broader curricular focus. In addition, I've added a section on professional development because the area of complementary and alternative medicine is an evolving area in health care that most faculty will not have addressed in any detail in their own schooling[24].

Organization: have summary statements about each section with links to "data" or more descriptive pieces.

1) Design: Curriculum goals and intentions

a) Philosophy and Mission of School of Nursing

b) Curriculum: specific courses

i) Syllabi

ii) Course assignments

Faculty interviews

2) Enactment: Teaching

a) Peer review

b) CAM Module

c) CAM case studies/fieldwork

d) Videotaped class sessions

e) Study guides

3) Results: Student Outcomes

a) SP videotapes

b) Student work?

4) Professional Development

a) Literature

b) Educational sessions

c) Participation in local, state, regional and national activities/organizations

d) Invitations to delivery papers

e) Publications/presentations

f) Other forms of scholarship

i) Clinical practice

ii) Research

The portfolio is a "vehicle for embodying the idea that excellent teaching is

teaching from which the teacher, too, learns; that is, teaching in which

faculty do not simply undertake the tasks of teaching but undertake them as

reflective practitioners interrogating their own practice and 'going public'

with their questions, findings, and new ideas"[25]

Weaknesses

Recommendations

Reflective/Personal Commentary

Scholarship is incomplete until it is understood by others. Lee Shulman argues that "reflecting on one's investigations in order to present them to others engages the scholar in deeper thinking about her findings, and hence a deeper understanding of her own work"[26]

1) How does this project come out of the needs of UW SoN FNP program?

2) How did it lead to changes in my thinking?

Resources

1) Portfolios

a) Edgerton, R., Hutchings, P., & Quinlan, K. (1991). The Teaching Portfolio:

Capturing the scholarship in teaching. Washington, DC: American Association

of Higher Education.

b) Hutchings, P. (1993). Campus use of the teaching portfolio:

Twenty-five profiles. Washington, DC: American Association of Higher Education.

c) Hutchings, P. (1996).Making teaching community

property: A menu for peer collaboration and peer review. Washington, DC:

American Association of Higher Education.

d) Hutchings, P. (Ed.) (1998).The course portfolio: How faculty can examine their teaching to advance practice and

improve learning. Washington, DC: American Association of Higher Education.

2) Complementary and alternative medicine

3) Nursing education

4) SoTL

Websites

Literature

Feedback Form

Acknowledgements

CASTL

CTE staff

InVISIBLEcollege funding

Chad Durr

Students, faculty at SoN

[1] Spencer, J. W. (1999). Essential issues in complementary/alternative medicine. In J. W. Spencer & J. J.Jacobs (Eds.), Complementary/alternative medicine: An evidence-based approach (pgs. 3-36). St. Louis: Mosby.

[2] Eisenberg, D. M., Davis, R. B., Ettner, S. L., Appel, S., Wilkey, S., Von Rompay, M. & Kessler, R. C. (1998). Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997. JAMA, 280, 1569-1575.

[3] Eisenberg, D. M. (1997). Advising patients who seek alternative medical therapies. Annals of Internal Medicine, 127, 61-69.

[4] Druss, B. G., & Rosenheck, R. A. (1999). Association between use of unconventional therapies and conventional medical services. JAMA, 282, 651-656.

[5] National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (1995). Advanced nursing practice: Curriculum guidelines and program standards for nurse practitioner programs. Washington, DC: Author.

[6] Wetzel, M. S., Eisenberg, D. M., & Kaptchuk, T. J. (1998). Courses involving complementary and alternative medicine at US medical schools. JAMA, 280, 784-787.

[7] Carlston, M., Stuart, M. R., & Jonas, W. (1997). Alternative medicine instruction in medical schools and family practice residency programs. Family Medicine, 29(8), 559-562.

[8] Is integrative medicine the medicine of the future? A debate between Arnold S. Relman, MD, and Andrew Weil, MD. (1999). Archives of Internal Medicine, 159, 2122-2126.

[9] Moylan, L. B. (2000). Alternative treatment modalities: The need for a rational response by the nursing profession. Nursing Outlook, 48, 259-261.

[10] Is integrative medicine the medicine of the future? A debate between Arnold S. Relman, MD, and Andrew Weil, MD. (1999). Archives of Internal Medicine, 159, 2122-2126.

[11] Eisenberg, D. M., Davis, R. B., Ettner, S. L., Appel, S., Wilkey, S., Van Rompay, M., & Kessler, R. C. (1998). Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997. JAMA, 280, 1569-1575.

[12] Egan, C. (2000).Providers of complementary and alternative medicine: Perceived role in U.S. health care and beliefs related to herbal medicine. Unpublished master's thesis. University of Wyoming, School of Nursing, Laramie, WY.

[13] Hutchings, P. (1996).Making teaching community property. A menu for peer collaboration and peer review. Washington, DC: American Association of Higher Education.

[14] Shulman, L. (1998). Course anatomy: The dissection and analysis of knowledge through teaching. In P. Hutchings (Ed.), The course portfolio: How faculty can examine their teaching to advance practice and improve student learning (pp. 5-13). Washington, DC: American Association for Higher Education.

[15] Hutchings, P. (1998). How to develop a course portfolio. In P. Hutchings (Ed.), The course portfolio: How faculty can examine their teaching to advance practice and improve student learning (pp. 47-55). Washington, DC: American Association for Higher Education.

[16] Hutchings, P. (1996). Making teaching community property. A menu for peer collaboration and peer review. Washington, DC: American Association of Higher Education.

[17] Shulman, L. (2000). Inventing the future. In P. Hutchings (Ed.), Opening lines. Approaches to the scholarship of teaching and learning (pp. 95-105). Carnegie Publications: Menlo Park, CA. [available on-line at CASTL site]

[18] Shulman, L. (1998). Course anatomy: The dissection and analysis of knowledge through teaching. In P. Hutchings (Ed.), The course portfolio: How faculty can examine their teaching to advance practice and improve student learning (pp. 5-13). Washington, DC: American Association for Higher Education.

[19] Hutchings, P. (1998).Defining features and significant functions of the course portfolio. In P. Hutchings (Ed.), The course portfolio: How faculty can examine their teaching to advance practice and improve student learning (pp. 13-18). Washington, DC: American Association for Higher Education.

[20] Hutchings, P. (2000). Approaching the scholarship of teaching and learning. In P. Hutchings (Ed.), Opening lines. Approaches to the scholarship of teaching and learning (pp. 1-10). Carnegie Publications: Menlo Park, CA. [available on-line at CASTL site]

[21] National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (2000). Domains and competencies of nurse practitioner practice. Washington, DC: author.

[22] Kligler, B., Gordon, A., Stuart, M., Sierpina, V. (2000). Suggested curriculum guidelines on complementary and alternative medicine: Recommendations of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Group on Alternative Medicine. Family Medicine, 31, 30-33.

[23] Hutchings, P. (1998). Defining features and significant functions of the course portfolio. In P. Hutchings (Ed.), The course portfolio: How faculty can examine their teaching to advance practice and improve student learning (pp. 13-18). Washington, DC: American Association for Higher Education.

[24] Edgerton, R., Hutchings, P., & Quinlan, K. (1991). The Teaching Portfolio: Capturing the scholarship in teaching. Washington, DC: American Association of Higher Education.

[25] Hutchings, P. (1998).How to develop a course portfolio. In P. Hutchings (Ed.), The course portfolio: How faculty can examine their teaching to advance practice and improve student learning (pp. 47-55). Washington, DC: American Association for Higher Education.

[26] Shulman, L. (2000). Inventing the future.In P. Hutchings (Ed.), Opening lines. Approaches to the scholarship of teaching and learning (pp. 95-105). Carnegie Publications: Menlo Park, CA.